I generally leave both performing closeup effects and the entertainment of children to folks who do those well. Not that I don’t do them well, I just don’t enjoy doing them as well as other aspects of performance magic. However, I had a planned week of visiting with four grown nieces, nephews, and their children where I would spend a day and dinner with each family and needed to perform for them. My father’s brother, my Uncle Ralph, had lived in the area I was visiting so to distinguish “which Uncle Ralph”, my family title had became “Magic Uncle Ralph” which obviously required that I do magic on the visit. I have fourteen nieces and nephews, twelve of them have children; eventually I’ve performed for all of them.

Here is the basic set that I developed and some thinking behind the pieces.

Some foundation questions and answers

When developing any routines or sets many questions have to be answered, like: “Why doing this, what kind of mood desired, age and interest of audience, how short or long is the performance, and what sort of interaction is desired.” I’ve also found it helpful to figure out “What does this lead into, how does this finish, or how do I get out of this?” These questions vary for each occasion but you do need to answer them beforehand in order to create better performances.

I wanted the young children to realize that someone in their extended family performed magic — for them at their dining table, so close that they touched it. I also desired they learn magic if they wanted. The effects needed to be very open and done with “common objects” which came from their home. The interest level needed to build from simple to more complex and end with skill beyond what they could find in beginning magic books. The kids ranged from six to twelve and my worst fear of having everything and every move touched and examined would be realized; the audience also contained two parents and my brother. I specifically set it up so we were gathered around the dining table where everything was informal and “unprepared”. Twenty minutes was my guess at the interest span except when I taught them how to do something; I also had more routines available if requested. Since I wanted to teach a simple magic move, the occasion would end with them doing and talking about magic — focused on them and not on me.

The Set, additional effects, and teaching

Considering what we call things

It is useful to think of routines in their basic-ness, useful to be able to get to their essence immediately. “Penny to Dime explains exactly what happens, “Coin and Knife through Napkin”, “Salt Shaker through Table” — however, those titles also explain what happens before it happens. So, we have to construct a Public Title. The Public Title takes on the explanation we wish the public remembers of how the magic occurs. Instead of “Coins Across” it becomes “Hole in the Hand”.

It’s respectful to credit the inventors and innovators who polish effects but counterproductive to do it too openly in public performances. In the wonderful instantaneous research possibilities with the internet, the commercial title of creations can be entered and “What will happen and How it is done” is in the hands of the audience before we take a breath after uttering that name. “Coins” “across” magic” results in 22 million results in less than a minute. The late 19th century conjurers solved this unknown problem of that era by giving overly colorful titles that could have applied to countless effects.

In this piece the basic title is generally used mainly because I’d like you to understand the routines and then come up with your own title (if necessary) to lead the audience to how you want them to remember the effect.

Constructing and planning the performance beforehand

I mentioned that it is also useful to “reverse plan” a longer set to: 1) figure how to introduce the pieces, 2) assure that the needed props are actually available in a “natural sequence”, and 3) check to see there is a logical progression to the effects. In this set I wanted to end with two surprising effects, one showing skill (the climax) and one that showed a surprise ending.

My “coins across” (“Hole in the Hand”) routine using four silver dollars worked well in this sort of an intimate setting, combined skill in mechanics and presentation; it could not be topped with any other impromptu effect. Somehow I needed to introduce the four silver dollars into the set and use one in another routine. “Penny to Dime” works well as an opening effect since it is casual but intriguing using small, inexpensive, and everyday coins. “It’s easier to see larger coins like these silver dollars, we’ll use them later”, introduces the larger coins and sets up the conclusion for coming back to those coins. “Salt shaker through table” needed a coin and was just the effect that ended with a bang and then relaxation. This led into “Hole in the Hand” dramatically — tension, relaxation, back to intense interest.

Salt shaker requires a napkin besides the coin and salt shaker. A glass could be used for this effect but I’ve always enjoyed the look and feel of a solid saltshaker and pouring salt onto the coin to make it dissolve. Therefore I needed a napkin and that meant doing napkin effects.

I had a large coin introduced and so “Coin thru napkin” was logical along with “Knife thru napkin”. Just needed a knife which is common at a table. Since I was going to be doing three napkin effects it seemed logical to have the napkin as the main character; the routines develop to make sure the napkin is a very ordinary and common fellow, like the people around the table.

Coins, salt shaker, napkin, knife all introduced logically and available.

Everyone thinks magicians do card tricks since cards tricks are what has been increasingly popular with magicians for 75 or more years. I let others do card tricks but do have a couple that I enjoy because they fit together and demonstrate two sides of my persona, magic happens to me and I’m skillful without being a showoff. So, I had those two prepared in the sense that I requested a deck of cards be available. I setup the “Laundry Trick” and gave the deck back to the parents saying, “Put these somewhere since we might need them.”

The angles required in “Laundry Trick” means the audience is in front and although it can be done seated, I choose to be standing for psychological reasons. The “confusion” of finding the cards, string, and scissors gives me a good chance to seat the audience, do the effect, and move to sitting to show the second card effect. How to get the audience and yourself where you want has to be planned (and made to appear spontaneous). There was only this one “angle concern” effect in the whole set so audience management became more of ensuring that everyone was comfortable and could see.

I requested a pair of scissors and yarn, string, or rope (about six feet) be available. I liked having the string and scissors found since that made the whole set more impromptu and “casual”. It also involved the kids helping to create the presentation plus cementing that there was nothing “gimmicky” about the props.

Basic Set:

- Produce coin somehow and exchange for larger coin,

- Napkin routine:

- Coin Through Napkin,

- Knife Through Napkin,

- Salt Shaker Through Table,

- “Hole in Hand” coins through hand.

- Additional Effects in case I needed them:

- Cards — simple effect and spelling card effect,

- Rope — “Shepherd’s Rope” and “Hunter’s Knot”.

- Teaching “French Drop” as an ending.

John Scarne’s 1951 “Scarne’s Magic Tricks” has good illustrations and explanation, many of the illustrations used here are from that book. Researching this article made me realize I had chosen classic pieces and most were described in some form or another in John’s book. I recommend it as a “advanced beginner’s book” in addition to “The Klutz Book of Magic” by John Cassidy and Michael Stroud..

Penny to Dime

I started with a simple “Penny to Dime” because it focused attention on only the youngest of the children sitting around the table and it was very intimate. I subtly moved the children to sit mostly to my left and the parents sitting across the table; this made it convenient for everyone to eventually move closer and remove the table as a barrier to their closeness. My Penny to Dime routine stresses “… attention and focus on penny regardless of what else happens around you” which quiets everyone down. When the dime is finally in the hand of the child, I then enlarge the performing space and include more people. Coins need to be large enough that all the audience can see them, so I quickly introduce the four silver dollars I need in the “coins thru hand” ending routine and make sure the dime stays with the person who did that magic. I use a piece of reindeer horn (“nubbin”) instead of a bland and gimmicky looking plastic thing; the gimmick needs to look “magical”, interesting, and not gimmick-ed.

Although vanishing a coin and then finding it behind a child’s ear is guaranteed to work, it was a little too “amateurish” and I wanted to teach a coin vanish at the end. Teaching a move that closely resembles something done in the performance might lessen the effect of what you did; teaching a move that could have been used, but wasn’t, reinforced the notion that magic involves skill and anyone can slowly learn the skill if they want to apply themselves.

In actual performance I realized the interest level was high and so I added the two card effects and the cut and restored rope effect just after I finished the “Penny to Dime” and introduced the dollars. I had to chat about what they had seen before in magic shows since now we had to find cards and some kind of rope (yarn) plus scissors; I had already made sure the napkins and salt shaker were handy. I’m undecided about having parents find items that may not be used in the performance, impromptu searching for stuff adds to the “reality” even if it extends and dilutes the intensity.

Card Effects

I actually enjoy the mental challenge of determining how and appreciate the skill needed to perform card effects. However, I find watching more than three card effects extremely boring; that’s probably why I don’t personally perform them. People enjoy card effects but get quickly saturated unless they are presented very very well. Children also don’t enjoy cards as much as adults do — and they are quick to demonstrate their boredom. I recommend you thoroughly examine why you present what you do, what the overall effect on the audience actually is, and then limit cards to two or three effects.

The two card effects I do perform are “Chinese Laundry” and “They Know Their Names” — they are explained in Thoughts on Cards. The first is a false failure “(“Erasing the Spot”, pgs. 202-203, Henry Hays’ “Learn Magic”, 1947) and makes me approachable but skillful, it leads into the more traditional “pick a card, it is lost, but we will find it” (a modest adaptation of Lewis Ganson’s “My Name — Your Name”, Routined Manipulation, Part One, 1950, pages 91 & 92, which Ganson adapted from Dr. Daly’s “Ad Lib Spelling”).

Henry Hay, the pen name of J Burrows Mussey, wrote “The Amateur Magician’s Handbook” that inspired a generation of magicians. “Learn Magic” (1947) was a general public book written prior to TAMH and my first magic book. Interestingly, on pgs. 79 -82 he teaches a version of “Spelling Master” where it probably soaked into my young subconscious mind.

Rope Effect

I added the cut and restored rope effect mainly because it was developed in the ’80s for my nieces and nephews and therefore connects the kids to the parents. Since it is a story and all actions are performed as the story unfolds I find it holds the interest of children and adults, I presently open theatrical performances with this effect. Stories which justify actions are so much more satisfying than just “explain the action” routines.

Basically “Shepherd’s Rope” is a “cut the rope in half” using your favorite method, plus “tie two loops with square knots”, “cut off the square knots”, and “wrap the rope around your hand removing the three knots” routine. The script will be in the book and pieces of that are elsewhere in these ramblings.

My favorite method of cutting the middle is a variation on #85 from Scarne’s Magic Tricks (1951) pgs 104 – 105.

Klutz Book of Magic pg. 65 has good illustration of square knots cut. Also the reminder to tie square knot snug but not tight — don’t tie granny knot.

Napkin Thoughts

The core of the evening’s entertainment consisted of the three effects using a napkin. Choice of napkins is very important since the napkin has to be big enough to allow the Knife Through Napkin effect to be done surrounded but small enough to not overshadow the coins in Coin Through Napkin. The napkin needs to be strong enough that it does not accidentally tear; it also needs to conform to and keep the shape of the salt shaker. If you are using paper napkins, a “Paper Rose” twisting might cement the innocence of the napkins; however, it might detract from the build that you are attempting — if you add a rose, I recommend it is done at the very beginning before the “Penny to Dime” where it won’t sidetrack the structure of the sets. Bruce Johnson’s “Napkin Rose” article is one of the best descriptions of this paper napkin effect, his webpage is an adaptation from his 2004 trilogy, “Creativity For Entertainers”.

Although all three napkin effects are “easy and simple to perform” they do require more practice than most of us want to put in. Getting the coin in position and naturally flipping the napkin takes muscle memory; letting the napkin untwist so the coin drops out is not natural and requires learning and practice; positioning the napkin so the channel is made easily and is covered requires muscle memory and thinking; opening the napkin after the penetration has to be natural; shaping the napkin around the shaker is essential; moving the napkin to several places without thinking requires muscle memory; creating an effective vanish of the shaker takes rehearsal; and revealing the shaker as part of the climax requires blocking and scripting.

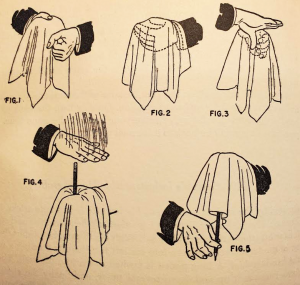

Coin Through Napkin

Coin Through Napkin is a simple adaptation of the Coin Through Silk presented in several standard texts.  [I’ll add good places like Rice’s and see if Joshua Jay has it in his book — Harry Lorayne has clear explanation on pgs. 201 -204 of his book ]. Using the larger dollar coin makes it more dramatic and visual. Since the flip move is essential and a larger amount of time is spent seeing the covered coin in this position, I recommend learning to place the coin off-center when you start so it will be centered after the flip. This takes learning, experimenting, lots of practice, and rehearsal — simple movements but the effect deserves perfection instead of sloppy.

[I’ll add good places like Rice’s and see if Joshua Jay has it in his book — Harry Lorayne has clear explanation on pgs. 201 -204 of his book ]. Using the larger dollar coin makes it more dramatic and visual. Since the flip move is essential and a larger amount of time is spent seeing the covered coin in this position, I recommend learning to place the coin off-center when you start so it will be centered after the flip. This takes learning, experimenting, lots of practice, and rehearsal — simple movements but the effect deserves perfection instead of sloppy.

Bruce Meyers showed me a move that justifies the coin penetrating the napkin and I’ll admit I thought it was the dumbest thing I had ever seen; audiences love it and now I use it all the time. After the twisting to secure the coin, Bruce used an imaginary pair of scissors to cut the center out of the napkin so there was a reason for the coin to drop through. Practice with different types of napkins (usually paper) will result in the dramatic drop and “clunk” of the coin meeting the table; cloth napkins often unfold quicker, cloth napkins are “starchy” and act quite unlike paper ones. Make sure to unfold the napkin to show it undamaged at the end; it also prepares the napkin for the Knife through Napkin.

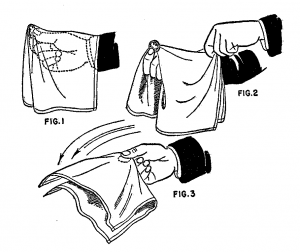

Knife Through Napkin

Although I have an extended opening for the Knife Through Napkin that involves questioning the difference between a “well in the ground” and a “hole in the ground” (a well has a bottom and a hole goes all the way through), I always have to decide whether it is worth it or just  skip to confirming there really is an invisible hole in the napkin. I was pleased to discover in Scarne’s Magic Tricks” pg 171 that he claims creation rights to this effect, #149 “Indestructible Handkerchief”; however he uses “thumb instead of forefinger — rather confusing and not as clean. I assume the forefinger moves are actually an improvement by someone; [add illustration from Scarne’s pg. 172]] Harry Lorayne’s 1977 “The Magic Book” has a great description of the finger moves in “Pen Through Handkerchief” (pgs. 249 – 252). [add two figures from Lorayne on pg. 249 & one from 250].

skip to confirming there really is an invisible hole in the napkin. I was pleased to discover in Scarne’s Magic Tricks” pg 171 that he claims creation rights to this effect, #149 “Indestructible Handkerchief”; however he uses “thumb instead of forefinger — rather confusing and not as clean. I assume the forefinger moves are actually an improvement by someone; [add illustration from Scarne’s pg. 172]] Harry Lorayne’s 1977 “The Magic Book” has a great description of the finger moves in “Pen Through Handkerchief” (pgs. 249 – 252). [add two figures from Lorayne on pg. 249 & one from 250].

Positioning the napkin so the channel can be made and thereafter having the napkin appear natural takes experimenting. I’ve found that one side of the napkin needs to be along the knuckles to thumb axis so the final result looks uniform; placing a corner instead of a side in this position exposes the device in the final result. More time and concentrated examination is made of this final result and so it needs to look natural. Poke forefinger in a little off-center and then holding fist, napkin, and finger upside down (pointing up) will result in the turning over of the hands covering the necessary move. The rest is just drama emphasizing the destroying of the napkin by shoving the knife through; the moment when the knife penetrates the cloth is important in the drama and twisting the knife to enlarge the hole so the handle goes through works well. I’ve enjoyed using fancy cloth napkins with steak knife in fancy restaurants while the server or manager is there, it is quite satisfying to assure them it was all illusion. Unfolding the napkin by crumpling it into a ball and then straightening out requires experimenting and practice. Again, smooth the napkin out so the set moves to Salt Shaker Through Table.

Salt Shaker Through Table

Both Coin Through Napkin and Knife Through Napkin have a large attention circle that moves to concentrated and then back to large, uses broad movements and wide arm placement, and generally plays to the whole table with a wide focus. Salt Shaker Through Table moves the focus to a much smaller circle; however, the focus circle needs to be controlled since the essential lapping move happens outside that circle. Dialogue and energetic movements direct the attention to that small circle, anything done outside that circle has to have no energy that will draw attention. Also, since lapping is involved, the angles are tricky and you have to practice lapping so it is comfortably “natural” and there are no “clunks”. How far you sit from the table edge is essential, your posture caused by leaning back and forth is critical to maintain naturalness, and critical to know where you want your elbows at all times.

Although I generally use a salt shaker, using an upside-down glass has interesting possibilities; however, this change requires much more experimenting, practice, and rehearsal to include the sound effects possible. Scarne’s book, pages 44-45, explain his simplified version of “The Spiritual Glass”.

My version of this routine explains that you can make the coin go through the tabletop using salt, pressure, concentration, and darkness. Sprinkle salt, put shaker over coin, and cover with napkin. Molding the napkin to the shaker is important. Each time after I try to push the coin I move the napkin to the edge of the table and then move it to (stage right) of the attention circle; I leave it there and concentrate attention to the coin, picking it up or poking it. The final time, I lap the shaker, move napkin shell stage right, don’t let got of it, and then try one more time with the frustrated slam down on the napkin. The timing of the silent script “…something is going to happen, // here it comes, // BLAM, // it happened, // lets see what happened.” enhances this climax. Revealing the shaker gone and either letting it be found on your lap or bring it out needs to be done quickly so the climax remains the main interest. [Klutz Book of Magic ppgs. 28 -30 has excellent outline and pictures of “Vanishing Salt Shaker” routine]

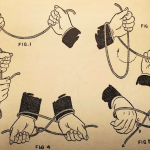

Coins Through Hand

My “Hole in My Hand” routine is an adaptation from Harry Lorayne’s 1977 “The Magic Book”. Years ago I looked for the simplest coin effect that was beyond my abilities and found Harry’s. It had to be done in-the-hands, no gimmicks, and with dollar coins. No palming since I’d not mastered that in 40 years and did not want to try at that time. It only involves two “moves” and a variation on one of those; I now like to call manipulation moves “mechanisms” since that term suggests they need to hidden and de-emphasized. I rediscovered a variation of the “click pass” since I did not understand how to do it and did not like Harry’s Pinch-Vanish. Of course I completely rewrote the script and changed the “moves from here to there” gestures. Lorayne’s “Four Coins Across” (pgs 179 – 185) uses finger-palm where I clip the coin with my finger tips when tossing the coins to the other hand and then put into my palm held (clipped) with the finger tips — a different tossing gesture changed the positions; that clip actually helped with the concluding Han Ping Chien move since it is the same with the added tossing and dropping. [maybe add figures149 & 150 for clip & finger-palm plus figs. 152 & 153 for Han Ping Chien. Klutz Book of Magic ppgs. 31 -33 does nice illustration of a variation of this move.]

Actually, any good coins across routine, even one done on the table, would work as the ending piece for the whole set. [find some places that have acceptable coins across routines.]

Teach French Drop

Closing remarks

Thanksgiving dinner

“Hunter’s Knot” illustration from Scrane’s Magic Tricks

poker party